http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2012/mar/08/older-viewers-rescuing-cinema

Link

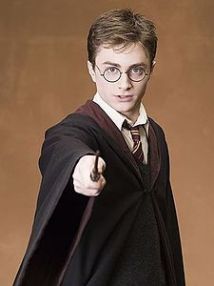

Synergy: Harry Potter (2001) and (2010)

2000 AOL and Times Warner merged.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher Stone:

Adverts of ‘Harry Potter and the Philosopher Stone’ shown on major American TV channels like HBO which is a subsidiary of Times Warner. The soundtrack was released by Atlantic Records part of Warner Music. Articles about the film were published in magazines etc owned by Time Warner. Games released for Game Boy and other PC games.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1:

A variety of teaser posters were released before the main poster. Website created allowing people to download the posters and also a ‘gallery’ section for people to download other movie shots. As well as teaser posters there were teaser trailers before the main trailer beginning the hype of the film. Huge media coverage for the premier. Merchandise has been created, replicating the wands and the magical sweets and chocolates for fans to buy. Hogwarts uniforms have been created also with collectors items for the older fan. The Wizarding World of Harry Potter has been created in Universal Studios America

IS HE a sorcerer or a multi-million-dollar branded media property? Harry Potter, J.K. Rowling’s boy wizard, whose first film is about to go on general release, boasts not only fictional magic powers. In the real world, he is the biggest test yet of claims made by AOL Time Warner, formed in a much-hyped merger at the start of 2001, that an integrated media conglomerate can conjure up spellbinding cross-promotion synergies.

AOL Time Warner does not own the publishing rights to the book. Nor does it own Ms Rowling, who reportedly earned £25m ($37m) last year. But it does own everything else to do with Harry Potter: the rights to the films (seven are planned) and all licensing and merchandising deals.

Thus the film—called “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” in Britain, but “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” in metaphysics-averse America—has been made by Warner Brothers, AOL Time Warner’s movie arm. The soundtrack has been recorded by Atlantic Records, a label from Warner Music Group. The film is on the cover of this week’sEntertainment Weekly, and an advance review appeared in Time magazine, both from the group’s publishing division. All the while, AOL websites have been promoting the film through games, competitions, sneak previews and advance bookings.

The case for the merger between AOL and Time Warner rested on a belief in this cross-promotional power. Harry Potter, argues Richard Parsons, AOL Time Warner’s co-chief operating officer, is a prime example of an asset “driving synergy both ways”. He explains that “we use the different platforms to drive the movie, and the movie to drive business across the platforms.” So, in America, AOL.com has offered subscribers the chance to win tickets to an advance screening; while in Britain, AOL has attracted new subscribers with the promise of tickets.

Certainly, it looks as if “Harry Potter” will be a tearaway success. Many observers expect its box-office take in America alone to reach $250m-300m, putting it in the blockbuster category (see table). With six more films to come, “this will be the most successful franchise in the history of Warner Brothers,” argues Mr Parsons. “It will be right up there with the Star Wars franchise—or maybe even bigger.”

Moreover, AOL Time Warner is set to make handsome profits. Ever since David Heyman, a British producer, sent an early copy of the first Harry Potter book to a fellow British studio honcho in Los Angeles, who persuaded his colleagues at Warner Brothers to pay some $500,000 for the rights, the studio has been sitting on a goldmine. Most of the film’s production costs have already been covered by merchandising deals, the biggest of which is with Coca-Cola. And the British cast of newcomers and established character actors come with a combined wage bill that would not even hire Tom Cruise.

Already, the studio’s standing within AOL Time Warner has risen. The film division is the only bit of the group for which Morgan Stanley, an investment bank, has revised its estimates of 2001 revenues significantly upwards—to $8.9 billion, or 23% of the total. Ms Rowling may have personally reined in the raw commercialisation of the brand: as Mr Parsons puts it coyly, “quite possibly, without her guidance we probably would have done different things.” Even so, the Potter franchise (including books) could bring in $1 billion.

The question remains whether such miraculous powers could still have been achieved if the two halves of AOL Time Warner had remained separate. No, reply its bosses: the heads of the various divisions, notorious for running their own fiefs in Time Warner days, would not think about “synergies” as much as they do when they are forced to sit together in a room every two weeks. Integration, they now argue, imposes creativity and encourages thinking in the group’s interest.

Yet even now, AOL Time Warner cannot fully exploit Harry Potter by itself. It has a deal, for instance, with Amazon.com to promote such toys as the LEGO Hogwarts classroom or Quidditch boardgame. Other media groups will benefit from Harry Potter too: BSkyB, part-owned by Rupert Murdoch’s NewsCorp, for example, has just extended a deal with Warner Brothers that should give it the British rights to show the films on pay-TV.

The best vindication of the AOL/Time Warner union is not cross-promotion as much as sheer muscle. With a classy property like Harry Potter, it would be hard not to conjure up success. But, at over twice the size of its nearest rival, Viacom, AOL Time Warner has massive clout. This gives it market leverage in any negotiation over the delivery of its brands down others’ pipes, or others’ down its own. Now that is power, if not of the magic sort.

Successful Low Budget Films

The Blair Witch Project (1999)

Budget $500,000–$750,000

Box Office $248,639,099

First-time feature filmmakers Directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez laid the groundwork for their shaky cam classic The Blair Witch Project with a creepy, early viral marketing campaign online. Their eerily true-to-life reports and interviews posted online sparked a theatrical sensation that left audiences wondering if the film they had just watched was really about missing teenagers, or just a piece of well-crafted fiction. The improvised performances added to the unsettling realism and also saved money in the duo’s estimated $25,000 budget. Sánchez and Myrick were aiming for a cable movie at most and after grossing a surprising $248,639,099 million worldwide, they had brought found footage-style films to the mainstream.

Inbetweeners (2011):

Budget $5.3 million

Box Office: $88,025,781

TV shows that become movies have a notoriously bad pedigree. Especially British comedy shows, which decide to send their cast off on holiday for their big screen adventure… Luckily, The Inbetweeners has never exactly played by the rules, first by becoming an unlikely foul-mouthed success, and then by going stratospheric at the box-office, notching up £44 million at UK cinemas and helping audience numbers actually rise last year. The film remained true to the series’ rather sweet ethos about what makes friendship, as well as finding a fitting ending to the story.

Beginners (2011):

Budget $3.2 million

Box Office $14,311,701

Told using an ambitious structure of flashbacks and flashforwards, Beginners follows Oliver (Ewan McGregor) as he deals with two events that rock his world; first, the fact his father has come out as gay, and then his subsequent cancer diagnosis and death. It wasn’t a surprise to me to learn that this was based on director Mike Mills’ person experience of his father coming out at the age of 75.

The thing this film has in bucket loads is heart, never straying into the saccharine despite being a romantic-comedy-drama. The film also includes a standard boy meets girl at party, boy and girl fall instantly head over heels in love sub-storyline, of which it’s so difficult to do anything new with, but their meeting is the best part of the film.

Submarine (2010):

Budget $1.5 million

Box Office $3 million

Shot in less than two months and on a small budget, this is a phenomenal directing debut from Richard Ayoade, and a truly British offering on this list. Based on the coming-of-age novel by Joe Dunthorne, Submarine charts 15-year-old Oliver Tate as he struggles with school, his first girlfriend Jordana (who has pyromaniac tendencies) and his attempts to save his parents’ failing marriage. Beautifully shot with a great soundtrack from Alex Turner (Arctic Monkeys) this film couldn’t more accurately stir up those forgotten memories of the self-indulgent, uncertain hell that being a teenage boy (or girl) was.

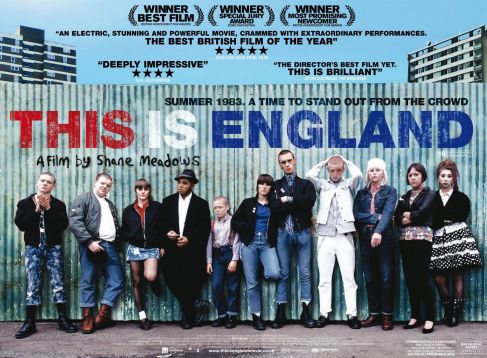

This is England (Case Study)

- Written and Directed by Shane Meadows (UK)

- Shane Meadows films include Once Upon a Time in the Midlands, Dead Man’s Shoesand Northern Soul

- Produced by EM Media (East Midlands)

- Distributed by Optimum (Independent UK Distributor : Brick, Vera Drake, Dead Man’s Shoes, 9 Songs)

- Additional Funding – Film4 and UK Film Council (£668,000 – New Cinema Fund, £90,000 P and A Fund)

- Theatrical Release: April 2007

- Independent British Film

- Genre/Tradition: Social Realism

- Critical Success: Film Festival Awards

- UK Box Office: £1.3m (gross), Casino Royale £55m (gross), The Queen £9m (gross). Projected successful DVD sales

- Production Costs: £1.2m

- Limited Distribution: UK Release (approx 100 Screens)

- BFI Category 1 (Culturally and Institutionally British)

- Low Production Values, no Star Marketing

Why significant:

British films became much more successful by appealing to British culture with independently made films, such as, “This Is England”. “This is England” is not the first successful film in Britain to appeal to British culture, but it is, certainly, one of the most iconic.

Meadows has made “This Is England” institutionally British by implementing themes of community, father figures, respect, friendship, local atmosphere, British icons, social realism, working class, ordinary people and his own childhood.

Shane Meadows gained funding for “This Is England” via multiple routes, all British, with Film 4 and the UK Film Council contributing a total of £758,000. By accepting funding from only British contributors, “This Is England” becomes even more iconic as a propeller to the British film industry.

Independent British films tend to use no star marketing and low budgets. “This Is England”, being institutionally British, agrees with these tendencies. The film uses actors which have not gained any attention for their talents. The no star marketing of the film allows the audience to be more engaged to the film more easily. However, despite adding to the British feel in the film, the low budget may not have been intended. The low budget shows that, although British film is catching up with Hollywood, they are seen as much more risky than the typical American mainstream film.

http://film.edusites.co.uk/article/this-is-england-case-study/

http://turnfordmedia.weebly.com/this-is-england-case-study.html

Warner Brothers and Fox Cross-Media Marketing

The Dark Night

Produced by Legendary Pictures (With Warner Bros)

Distrubuted by Warner Bros

Directed by Christopher Nolan

- A website was set up as a fake promotion website for a character in the Batman called ‘Harvey Dent’ – the page was meant to be his political campaign

- People would sign up with their email address

- They then would have to do something like hold up posters that could be printed from the website and take a photo and upload it

- Warner Bros invited fans to follow a ‘case of clues’ to track down the Joker

- This included a van going around some cities trying to gain ‘promotion’ for Harvey Dent where fans would received tshirts and other things

- Collected DVD’s in papers

- Badges created

Fox

- Works with a lot of other companies to create a film together

- Fox Searchlight Pictures is a subsidiary of 20th Century Fox that focuses on independent, British and subtitled films. With great films like 28 Days Later, 28 Weeks Later, Boys Don’t Cry, Black Swan, Slumdog Millionaire and many more, they have distributed some of the most successful indie films made, with the most notable being Slumdog Millionaire and Black Swan, grossing over $200,000,000.

- Searchlight has produced a film called ‘Boys Don’t Cry

- But this was a good move for Searchlight because the film as a whole won 43 awards and was nominated for a further 27 other awards, so a huge success which could help build Searchlight’s reputation for distributing award winning movies.

- Fox’s Family Guy, produced an episode called ‘Boys Do Cry’ which was a parody of the film

- This could be a subtle use of synergy, even though it was made a while after the film.

- Also in Family Guy there are many references to Star Wars and there are even 3 extra long parodies of Star Wars

- X-Men Films

- The poster campaign features an exclusive movie trailer and a link to the X-Men film’s Facebook ‘like it’ which is accessed by tapping an NFC-enabled smart phone on poster sites around London. Each site has a pre-programmed NFC chip affixed to the rear of the poster.

- 20th Century Fox wanted the latest in innovative out-of-home marketing to promote the upcoming X-Men movie. The campaign was aimed at engaging those in the advertising industry to the potential benefits NFC offers brands when interacting with their customers.

- Proxama joined forces with JCDecaux and Posterscope to deliver the UK’s first NFC outdoor marketing campaign for the movie, offering consumers exclusive video content and a link to the Facebook fan page with a simple tap of a poster on bus shelters located in the heart of London.

Each site had a pre-programmed NFC chip affixed to the reverse of the poster. This was a URL-based campaign which linked to the content via a website landing page.

How New Technologies Have Changed The Film Industry (Production)

Peter Jackson to shoot The Hobbit with new film technology

Director Peter Jackson is to shoot The Hobbit using technology in a way that analysts believe could revolutionise the film industry.

The move breaks with nine decades of cinema tradition.

Sir Peter likens the moment to digital CDs supplanting vinyl records, claiming the technology will produce “hugely enhanced clarity and smoothness” and more lifelike images.

Announcing the decision on his Facebook page, he says: “Looking at 24 frames every second may seem okay, and we’ve all seen thousands of films like this over the last 90 years.

“But there is often quite a lot of blur in each frame, during fast movements, and if the camera is moving around quickly the image can judder.”

The Oscar-winning director argues that the technique will enable audiences to comfortably watch two hours of 3D footage without getting eyestrain.

He said Warner Bros production studio supports the move, amid predictions that 10,000 cinema screens will be capable of showing the new format by the film’s release date of December 2012.

“We are hopeful that there will be enough theatres capable of projecting 48fps by the time The Hobbit comes out, where we can seriously explore that possibility with Warner Bros,” Sir Peter said.

Most modern digital projectors could be adapted to the task if their servers are given software upgrades.

An industry-wide move to the higher speed also has a strong advocate in James Cameron, who directed the 2009 science fiction epic Avatar in 3D.

Cameron has said he is planning to shoot the sequel Avatar 2 at 48 frames per second.

But the development is likely to upset film purists, who Sir Peter says will criticise “lack of blur and strobing” — what one industry commentator has likened to art historians lamenting the loss of grainy, characterful darkness when an Old Master canvas is cleaned.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that we’re heading towards movies being shot and projected at higher frame rates,” Sir Peter said.

“It looks great, and we’ve actually become used to it now, to the point that other film experiences look a little primitive.”

Shooting of the £315 million Hobbit, in which Martin Freeman from The Office plays Bilbo Baggins, started last month at Sir Peter’s Wellington studios.

How New Technologies Have Changed The Film Industry (Distribution)

How Digital Is Changing the Nature of Movies

“The Master,” with Joaquin Phoenix, and Philip Seymour Hoffman, was shot in 70 millimeter.

IN the beginning there was light that hit a strip of flexible film mechanically running through a camera. For most of movie history this is how moving pictures were created: light reflected off people and things would filter through a camera and physically transform emulsion. After processing, that light-kissed emulsion would reveal Humphrey Bogart chasing the Maltese Falcon in shimmering black and white.

Gregg Toland, cinematographer, behind the camera with the director Orson Welles on “Citizen Kane.”

More and more, though, movies are either partly or entirely digital constructions that are created with computers and eventually retrieved from drives at your local multiplex or streamed to the large and small screens of your choice. Right before our eyes, motion pictures are undergoing a revolution that may have more far reaching, fundamental impact than the introduction of sound, color or television. Whether these changes are scarcely visible or overwhelmingly obvious, digital technology is transforminghow we look at movies and what movies look like, from modestly budgeted movies shot with digital still cameras to blockbusters laden with computer-generated imagery. The chief film (and digital cinema) critics of The New York Times, Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott, look at the stuff dreams are increasingly made of.

A. O. SCOTT In Jean-Luc Godard’s 1986 movie “Keep Up Your Right” a movie director (played by Mr. Godard) declares that “the toughest thing in movies is carrying the cans.” Those once-ubiquitous, now increasingly quaint metal boxes contained the reels of exposed celluloid stock that were the physical substance of the art form. But nowadays the easiest thing in digital movies might be carrying the hard drive or uploading the data onto the server. Those heavy, bulky canisters belong to the mechanical past, along with the whir of the projectors and the shudder of the sprockets locking into their holes.

Should we mourn, celebrate or shrug? Predigital artifacts — typewriters and record players, maybe also books and newspapers — are often beautiful, but their charm will not save them from obsolescence. And the new gizmos have their own appeal, to artists as well as consumers. Leading manufacturers are phasing out the production of 35-millimeter cameras. Within the next few years digital projection will reign not only at the multiplexes, but at revival and art houses too. According to an emerging conventional wisdom, film is over. If that is the case, can directors still be called filmmakers? Or will that title be reserved for a few holdouts, like Paul Thomas Anderson, whose new film, “The Master,” was shot in 70 millimeter? It’s not as if our job has ever been to review the coils of celluloid nestled in their cans; we write about the stories and the pictures recorded on that stock. But the shift from photochemical to digital is not simply technical or semantic. Something very big is going on.

MANOHLA DARGIS Film isn’t dead yet, despite the rush to bury it, particularly by the big studios. Film does not have to disappear. Film isn’t broken — it works wonderfully well and has done so for a century. There is nothing inevitable or natural about the end of film, no matter how seductive the digital technologies and gadgets that are transforming cinema. A 16-millimeter film camera is plenty cool. A 35-millimeter film image can look sublime. There’s an underexamined technological determinism that shapes discussions about the end of film and obscures that the material is being phased out not because digital is superior, but because this transition suits the bottom line.

The end of film isn’t a just a technological imperative; it’s also about economics (including digital rights management). In 2002 seven major studios formed the Digital Cinema Initiatives (one later dropped out), the purpose of which was “to establish and document voluntary specifications for an open architecture for digital cinema that ensures a uniform and high level of technical performance, reliability and quality control.” What these initiatives effectively did was outline the technological parameters that everyone who wants to do business with the studios — from software developers to hardware manufacturers — must follow. As the theorist David Bordwell writes, “Theaters’ conversion from 35-millemeter film to digital presentation was designed by and for an industry that deals in mass output, saturation releases and quick turnover.” He adds, “Given this shock-and-awe business plan, movies on film stock look wasteful.”

SCOTT Let me play devil’s advocate, though I hope that doesn’t make me an advocate for the corporate interests of the Hollywood studios. If there is a top-down capitalist imperative governing the shift to digital exhibition in theaters, there is at the same time a bottom-up tendency driving the emergence of digital filmmaking.

Throughout history artists have used whatever tools served their purposes and have adapted new technologies to their own creative ends. The history of painting, as the art critic James Elkins suggests in his book “What Painting Is,” is in part a history of the changing chemical composition of paint. It does not take a determinist to point out that artistic innovations in cinema often have a technological component. It takes nothing away from the genius of Gregg Toland, the cinematographer on “Citizen Kane,” to note that the astonishing deep-focus compositions in that film were made possible by new lenses. And the arrival of relatively lightweight, shoulder-mounted cameras in the late 1950s made it possible for cinéma vérité documentarians and New Wave auteurs to capture the immediacy of life on the fly.

Long before digital seemed like a viable delivery system for theatrical exhibition, it was an alluring paintbox for adventurous and impecunious cinéastes. To name just one: Anthony Dod Mantle, who shot many of the Dogma 95 movies and Danny Boyle’s zombie shocker“28 Days Later,” found poetry in the limitations of the medium. In the right hands, its smeary, blurry colors could be haunting, and the smaller, lighter cameras could produce a mood of queasy, jolting intimacy.

Image quality improved rapidly, and the last decade has seen some striking examples of filmmakers exploring and exploiting digital to aesthetic advantage. The single 90-minute Steadicam shot through the Hermitage Museum that makes up Alexander Sokurov’s“Russian Ark” is a specifically digital artifact. So is the Los Angeles nightscape in Michael Mann’s “Collateral” and the rugged guerrilla battlefield of Steven Soderbergh’s “Che,” a movie that would not exist without the light, mobile and relatively inexpensive Red camera.

Digital special effects, meanwhile, are turning up this season not only in phantasmagorical places like “Cloud Atlas” and “Life of Pi,” but also in movies that emphasize naturalism. To my eyes the most amazing bit of digital magic this year is probably the removal of Marion Cotillard’s legs — including in scenes in which she wears a bathing suit or nothing at all — in Jacques Audiard’s gritty “Rust and Bone.” While movie artists of various stripes gravitate toward the speed, portability and cheapness of digital, which offers lower processing and equipment costs and less cumbersome editing procedures, consumers, for their part, are suckers for convenience, sometimes — but not always — at the expense of quality.

I love the grain and luster of film, which has a range of colors and tones as yet unmatched by digital. There is nothing better than seeing a clean print projected on a big screen, with good sound and a strong enough bulb in the projector. But reality has rarely lived up to that ideal. I spent my cinephile adolescence watching classic movies on spliced, scratched, faded prints with blown-out soundtracks, or else on VHS — and also not seeing lots of stuff that bypassed the local repertory house or video store. I’d rather look at a high-quality digital transfers available on TCM or from the Criterion Collection, and more recently (very recently) at a revival theater like Film Forum in New York. Like anyone else of a certain age I have fond memories of the way things used to be, but I also think that in many respects the way things are is better.

DARGIS We’re not talking about the disappearance of one material — oil, watercolor, acrylic or gouache — we’re talking about deep ontological and phenomenological shifts that are transforming a medium. You can create a picture with oil paint or watercolor. For most of their history, by contrast, movies were only made from photographic film strips (originally celluloid) that mechanically ran through a camera, were chemically processed and made into film prints that were projected in theaters in front of audiences solely at the discretion of the distributors (and exhibitors). With cameras and projectors the flexible filmstrip was one foundation of modern cinema: it is part of what turned photograph images into moving photographic images. Over the past decade digital technologies have changed how movies are produced, distributed and consumed; the end of film stock is just one part of a much larger transformation.

I’m not antidigital, even if I prefer film: I love grain and the visual texture of film, and even not-too-battered film prints can be preferable to digital. Yes, digital can look amazing if the director — Mr. Soderbergh, Mr. Mann, Mr. Godard, David Fincher and David Lynchcome to mind — and the projectionist have a clue. (I’ve seen plenty of glitches with digital projection, like the image freezing or pixelating.) I hate the unknowingly ugly visual quality of many digital movies, including those that try to mimic the look of film. We’re awash in ugly digital because of cost cutting and a steep learning curve made steeper by rapidly changing technologies. (The rapidity of those changes is one reason film, which is very stable, has become the preferred medium for archiving movies shot both on film and in digital.)

We’re seeing too many movies that look thin, smeared, pixelated or too sharply outlined and don’t have the luxurious density of film and often the color. I am sick of gray and putty skin tones. The effects of digital cinema can also be seen in the ubiquity of hand-held camerawork that’s at least partly a function of the equipment’s relative portability. Meanwhile digital postproduction and editing have led to a measurable increase in the number of dissolves. Dissolves used to be made inside the camera or with an optical printer, but today all you need is editing software and a click of the mouse. This is changing the integrity of the shot, and it’s also changing montage, which, in Eisenstein’s language, is a collision of shots. Much remains the same in how directors narrate stories (unfortunately!), yet these are major changes.

SCOTT I agree that digital has introduced new visual clichés and new ways for movies to look crummy. But there have always been a lot of dumb, bad-looking movies, and it’s a given that most filmmakers (like most musicians, artists, writers and humans in whatever line of work) will use emerging technologies to perpetuate mediocrity. A few, however, will discover fresh aesthetic possibilities and point the way forward for a young art form.

An interesting philosophical question is whether, or to what extent, it will be the same art form. Will digitally made and distributed moving-picture narratives diverge so radically from what we know as “films” that we no longer recognize a genetic relationship? Will the new digital cinema absorb its precursor entirely, or will they continue to coexist? As dramatic as this revolution has been, we are nonetheless still very much in the early stages.

DARGIS The history of cinema is also a history of technological innovations and stylistic variations. New equipment and narrative techniques are introduced that can transform the ways movies look and sound and can inspire further changes. Does taking film out of the moving image change what movies are? We don’t know. And it may be that the greater shift — in terms of what movies were and what they are — may have started in 1938, when Paramount Pictures invested in a pioneering television firm. By the late 1950s Americans were used to watching Hollywood movies on their TVs. They were already hooked on a convenience that — as decades of lousy-looking home video confirmed — has consistently mattered more to them than an image’s size or any of its other properties.

From there it’s just a technological hop, skip and jump to watching movies on an iPad. That’s convenient, certainly, but isn’t the same as going to a movie palace to watch, as an audience, a luminous, larger-than-life work that was made by human hands. To an extent we are asking the same question we’ve been asking since movies began: What is cinema? “The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent,” the philosopher Roland Barthes wrote. “From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here.” A film image is created by light that leaves a material trace of something that exists — existed — in real time and space. It’s in this sense that film becomes a witness to our existence.

Then again, I learned from the great avant-garde artist Ken Jacobs — who projects moving images that he creates with shutters, lenses, shadows and his hands — that cinema doesn’t have to be film; it has to be magic.

How New Technologies Have Changed The Film Industry (Exhibition)

New 3D Glasses are much sharper and have better effects, increasing the number of people coming to the cinema. Now however researchers in South Korea have discovered a new way for moviegoers to enjoy 3-D movies without the hassle of wearing the bulky glasses.

Engineers at the Seoul National University have proposed using one projector on a modified screen to achieve a 3-D experience instead of the traditional two projectors.

The trick, according to researchers. is said to be a special filter that is placed directly opposite the projector to essentially block vertical regions of the screen. This would result in a slightly different, offset picture being sent to each eye.

Traditionally, when watching a 3-D film, two projectors are being used at once-ultimately displaying two images from two films on the same screen all at the same time. This can explain why the screen may appear to be fuzzy and distorted when the 3-D glasses are removed.

The new method would be similar to the method used for the Nintendo DS, where a filter enables the left-projector movie to be viewed by your left eye and for the right-projector movie to be viewed by your right eye.

The movie screen is covered in a special film that removes any need to wear traditional 3D glasses. The light-blocking technique means that resolution isn’t as strong as an unfiltered projection, but the technique is reportedly still being developed.

The new method would allow movie theaters to keep their projectors where they’ve always been, behind the audience, and uses fairly simple optical technology.

Lead scientist Byoungho Lee said that this method “might constitute a simple, compact, and cost-effective approach to producing widely available 3D cinema, while also eliminating the need for wearing polarizing glasses.”

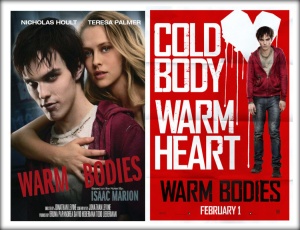

How New Technologies Have Changed The Film Industry (Marketing)

The vide o sharing website Youtube now broadcasts trailers of new films before some popular videos. While searching for other videos the trailer for ‘Warm Bodies’ played before a video started. Through new technology of the internet and social media sites it allows films to be easily marketed and viewed by millions of people. By showing a short film trailer before a video allows people to be made aware of the film and while using the internet they can search elsewhere for the film including websites like IMDB. People can now view films on portable devices like tablets, anywhere in the world. Films can be uploaded onto small devices and watched; the use of internet has now made it easier to view films, both legally and illegally including sites like Love Film and Netflix where people can pay for films and download them or have them delivered. With new technology arising more and more people are choosing to download films through the internet as it is more convenient and sometimes cheaper.

o sharing website Youtube now broadcasts trailers of new films before some popular videos. While searching for other videos the trailer for ‘Warm Bodies’ played before a video started. Through new technology of the internet and social media sites it allows films to be easily marketed and viewed by millions of people. By showing a short film trailer before a video allows people to be made aware of the film and while using the internet they can search elsewhere for the film including websites like IMDB. People can now view films on portable devices like tablets, anywhere in the world. Films can be uploaded onto small devices and watched; the use of internet has now made it easier to view films, both legally and illegally including sites like Love Film and Netflix where people can pay for films and download them or have them delivered. With new technology arising more and more people are choosing to download films through the internet as it is more convenient and sometimes cheaper.